Japan on My Mind Japan on My Mind

by Mairéid Sullivan

May 2011

Photos by Roger Hammond

The shakuhachi is Anne Norman’s voice. She ‘sings’ the pure voice of the shakuhachi with the sense of freedom and sheer ecstasy of a gifted singer! I don't remember ever hearing any instrument play such pure voice-like tones!

The shakuhachi first came to Japan during the Nara period (710-794) from Tang China, more than 1,000 years ago. Many different approaches to playing the shakuhachi have evolved through highly refined musical styles and bear the names of the founders of respective schools.

Meian-ryu is the oldest school of shakuhachi playing and is inseparable from the original doctrine of ‘blowing Zen'. Zen-Buddhism practitioners often prefer to play the shakuhachi, rather than reading sutras, to achieve Enlightenment (satori). ‘Itton Jobutsu' - Buddha is hidden in one sound - is a saying of Fuke monks. Anne Norman's style is natural, looking for a quality and purity of sound in each and every note.

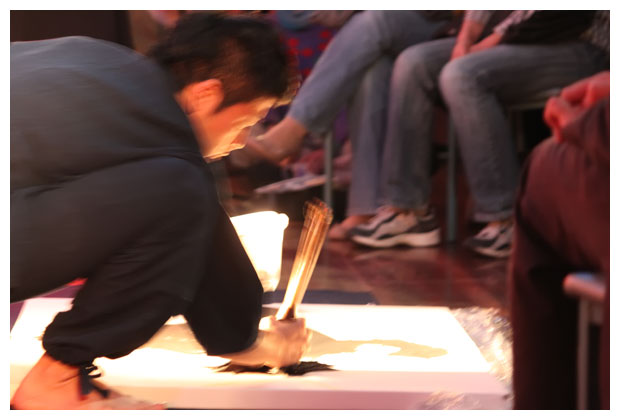

Anne recently curated a brilliantly conceived mini-exposition on Japanese culture here in Melbourne, Japan on My Mind —an adventurous program of calligraphy ‘performance’ set to music, dance, songs, spoken word and a traditional tea ceremony— a rare intimate insight into deeply cultivated artistic sensibility in Japanese culture.

Here is an excerpt from the extensive concert program notes:

The Ueda Soko Tradition places particular emphasis on developing the sincerity of the host; developing a reverence and joy for one’s own life, developing Zen values through all the activities of the tea ceremony; and cultivating beauty that is austere, minimal, yet elegant.

I was particularly thrilled to be sitting right next to the koto player when she performed at the back of the hall, accompanying the calligraphy performance during the second half of the concert. You can learn more by visiting Anne Norman's website: http://annenorman.com/

I had two questions for Anne when I met with her after the performance.

Mairéid Sullivan: Can you articulate the feelings you experience when playing the instrument?

Anne Norman: I do! Sonically. Whether I can express that verbally however... Anne Norman: I do! Sonically. Whether I can express that verbally however...

For me shakuhachi is my voice. I can’t sing well with my voice box (I wish I could), but through my breath and lips I can ‘sing’ and express a depth of emotional response to the written music and the composers possible intent; to my own interpreted agenda of meaning; or in spontaneous response to an improvised gesture by a musician or dancer. I have also given a recital in response to works of art hanging in a gallery, where the artist asked me to take the folk attending the exhibition opening to stand before works that moved me, and I created spontaneous works on shakuhachi which I felt expressed the visual poetry of colour and form before me. So my ‘feelings’ when playing shakuhachi are fairly emotionally expressive, but my head is in an abstract wordless sonic world. I rarely paint a narrative journey on shakuhachi. I am thinking and expressing purely in sound colour, texture and melodic gesture. If I am put into a situation where I am coupled with a performer who is more intellectually propelled, who wishes to convey cleverness or who stays rigidly within a particular paradigm such as ‘a blues progression’ or a contrived atonality, or one who is not emotionally responsive or sensitive to the need for silence and space between the sounds... then I am usually uncomfortable and my feelings are not an outpouring of sonic emersion, but an intellectual attempt to engage with an inner cry of “get me out of here!” I enjoy touching on intellectual or prescribed elements however, but like to be free to move on, and preferably do that with someone who is sensitive to the other.

Mairéid Sullivan: Why and when did you choose the instrument?

Anne Norman: Why? Cause it was there, and I was in Japan. When? In 1986, while living in Japan. It was merely a hobby. Not serious, but by 1988 I was pretty focused on shakuhachi. I then received a string of scholarships in Australia and Japan all helping me further my obsession with this frustratingly difficult instrument to get the sound I wanted in order to express myself! It was its breathy and timbrally broad palette that made me put aside the flute which I had done my music performance degree on, and begin the process of pulling one well established embouchure apart in order to find another. The notion that each note is unique and different from its neighbouring notes was freeing. I had spent years practicing to make all notes qualitatively ‘equal’. Now I was encouraged to find the unique character of the resultant sound of a particular fingering. Having 3 different ways to play the note Ab is fabulous, and while the pitch is ostensibly the same, every other aspect of the note is imbued with a specific personality, if you will. One may be veiled, the other rough, one breathy, another wirey...

I think the shakuhachi chose me. I like silence. And shakuhachi is all about sculptured silence. Actually, that is the name of an album I am working towards. I generally never listen to music at home. I live in silence, except when I practice. And then the echoing sounds of what I have been playing keep resounding in my head, as there are no conflicting other sounds. Its not that I don’t enjoying listening to music, I just don’t often set the time aside to sit down and concentrate on listening, and I don’t like background music. But when I do put an evening aside to listen, it is magic to go into the world of a specific composer, or a specific performer and listen to the language they use.

back to top

Japan on My Mind

Friday 13th May, 2011

Presented by the Boite at Box Hill Community Arts Centre, Box Hill

| Satsuki Odamura |

koto |

| Anne Norman |

shakuhachi |

| Melanie Robinson |

cello |

| Adam Wojcinski |

Ueda Soko Tea Ceremony |

| Philip Flavin |

shamisen, voice |

| Susan Taylor |

jiuta-mai dance |

| Shingo Nozao |

calligraphy and ink art |

| Leigh Sloggett |

netsuke artist |

Programme

On the Wing koto solo

A kestrel, a lacewing, an eel cello solo

Little Fish cello solo

Aki no Yama uta / Morton Bay Morph shakuhachi and cello

In the moment cello and shakuhachi duo impro

Brush Strokes koto, cello and shakuhachi impro with live ink art

INTERVAL

Please take this time to meet with Leigh and ask him about his exquisite Netsuke miniature carvings; talk with Shingo and perhaps buy some of his artworks or calligraphy cards; buy one of the musicians CDs… or simply relax and have a cuppa and something wonderful to eat.

Ueda Soko tea ceremony with koto accompaniment

Cha ondo jiuta-mai dance with shamisen, voice and shakuhachi with the simultaneous calligraphy of these ancient lyrics

Hoshun duo for koto and shakuhachi

NOTES on the Pieces:

Tubasa ni notte On the Wing by Tadao Sawai (1986) Tubasa ni notte On the Wing by Tadao Sawai (1986)

On the Wing is a solo koto by Satsuki’s teacher, expressing his preoccupation with flight. Humans have always been drawn to the sky and the clouds and have dreamt of being able to fly like a bird. This piece consists of three small pieces, labelled Running, Floating and Leaping.

A kestrel, a lacewing, an eel is a piece written by the performer, Melanie Robinson in March this year during a creative development for the play "The Ghost's Child" based on a novel by Sonya Hartnett. Sonya's work is visual and visceral, and inspires the same in sound. Little Fish is a reworking of a traditional Australian folk song.

Aki no Yama uta Mountain Song of Autumn is a folk song from Miyagi prefecture, where the Sendai earthquake was centred. It features the warbling vocal technique of the region. Performed on shakuhachi and segueing into a fantasy on the Australian folk tune Morton Bay with cello. Anne has shifted the modality of the Australian tune, producing a whole new melody, and then returning to a glimpse of the Autumnal mountains of Miyagi.

Cha ond Song of Tea music by Kikuoka Kengy (1830)

Cha-ond? belongs to a genre of music known as tegoto-mono, characterised by lengthy instrumental interludes nestled between sections of text. The author of the text, Yokoi Ya (18th century), was a well-known author with a sensitive and astute mind delighting in the foibles of humanity. In tonight’s piece, Yokoi’s lyrics betray a surprising streak of humour and word play. Instead of the usual double entendre, Cha-ond has three levels of meaning. Embedded throughout the text is jargon taken from the pleasure quarters, all of which are erotic. (Tea, for one choice example, can mean female genitalia.) The lyrics therefore echo with subtle meanings beyond the expected images of Japanese poetry. (Doubtless, Yokoi would have found the translator’s predicament, a source of great amusement. Only one level is given here.)

Cha ondo Lyrics by Yokoi Yay

Yo no naka ni / sugurete hana wa Yohino-yama / momiji wa Tatsuta / cha wa Uji no miyako no tatsumi / sore yori mo sato wa miyako no hitsuji saru / suki to wa tare ga na ni tateshi / koicha no iro no fukamidori / matsu no kurai ni kurabete / kakoi to iu mo hikukeredo / nasake wa onaji tokokazari / kazaranu mune no ura omote / fukusa sabakenu / kokoro kara kikeba / omowaku chigaidana / te dshite kbako / hishaku no take wa sugu naredo / sochi wa chashaku no yugami moji

Instrumental Interlude

back to top

Uwa o harashi no / hatsu mukashi / mukashi no jiji baba to naru made / kama no naka samezu / en wa kusari no sue nagaku / chiyo yorozu e

Those things surpassing in this world / the cherry blossoms of Mt. Yoshino / the maple leaves of Tatsuta / the tea of Uji to the Southeast of the capital / yet more surpassing is tea of the village to the Southwest of the capital / who started this rumour of our love? / the deep green of the powdered tea / compared to the heights of the pine, I am nothing / but passions do not change / my heart is without artifice / hearing of you / I was as mistaken and you are as crooked as the tearoom’s staggered shelves / we meet and I ask you why this is so / I am as straight as a ladle while you are as crooked as a tea scoop.

The hatsumukashi tea dispels my gloom / together we age and become the old couple that talk of the past, and, like a tea kettle, are always warm / our love will be as long as the tea kettle chain / for one thousand, ten thousand years!

Hshun Spring Bursts Forth by Nagasawa Katsutoshi (1971)

An evocation of spring and new life. A beautiful interplay of koto and shakuhachi, depicting the new growth and sounds of nature at the beginning of Spring. Nagasawa was a modernist composer of classical Japanese music writing for traditional Japanese instruments. He was one of the founding members of Pro Musica Nipponia in 1964.

NOTES on the Artists: NOTES on the Artists:

Satsuki Odamura is a Japanese koto virtuoso who has pioneered the teaching and performing of koto in Australia. She was taught at the Sawai Koto School of Music in Tokyo by legendary koto players Tadao and Kazue Sawai, gaining her Shihan or master license in 1985. Three years later, she moved to Australia and has since inspired a number of Australian composers to write for her instrument and has worked with a number of musicians from other genres, including jazz and classical. She is a member of the world music group Waratah with Sandy Evans and Tony Lewis, the contemporary music ensemble Elision and the trio PRRIM with Tunji Beier and Adrian Sherriff. Satsuki has performed with a number of symphony and chamber orchestras in Australia, including the renowned Australian Chamber Orchestra (ACO). She has recorded three of her own albums in collaboration with Australian musicians and, in the process, has found new and exciting contexts for this traditional Japanese instrument. Her most recent CD, Koto Dreaming, was released in 2006. satsukikoto.com.au

Melanie Robinson, cellist, singer, composer and arranger, is best known for her collaborations with Tim Rogers and original duo Mr Sister. She also writes / records for and performs with an array of contemporary Australian musicians including Washington, John Butler Trio, The Audreys, William Barton and Leah Flanagan. Melanie has been recipient of the ArtsWA Young Artist Fellowship, Pauline Steele prize for solo cello performance and two-time winner of the WAMI Best Female Instrumentalist. “A heart-stopper” (Sydney Morning Herald), with “a voice that will make your black heart beat again.” (AdelaideNow)

Anne Norman is a shakuhachi performer working in a diverse range of music creation. Anne took up the shakuhachi in 1986 in Japan, eventually studying three lineages of shakuhachi music including a period on scholarship at Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music under Yamaguchi Goro. Anne is featured on many CDs and has performed with a variety of artists in concerts and festivals in Australia, Europe, America and Japan. During the last few years, Anne has authored a book on tea entitled Curiosi-tea, and is increasingly being booked for Camellia Cha performances. She also tours the country performing in duo with taiko drummer Toshi Sakamoto and as a solo storyteller in schools, incorporating live music into multi-media, interactive narrative performances of modified Japanese folk tales. AnneNorman.com and CamelliaCha.com

Shingo Nozao is a calligrapher working in many mediums. In addition to exhibitions, he performs live calligraphy with music and multi-media, and he also works in several movie studios in Japan… his hands are quite famous in movies when the hero pens a letter or piece of poetry. Shingo says his art works of calligraphy are based on his own peculiar Japanese ‘frustration’, where the delicacy and dynamic of his emotions can be expressed in his calligraphic art works. Shingo is based in Osaka.

Adam Wojcinski is the Melbourne instructor of the Ueda Sko Ry Tradition of Japanese Tea Ceremony - a tradition founded in Hiroshima in the early 1600s by the samurai warlord Ueda Sko. Adam studied tea in Hiroshima and returns there every year to continue his training in the life long journey of Chanoyu. Adam is intensely interested in the Samurai values, Zen thought, and aesthetic sensibility woven into his Tradition of Tea. Adam is the first English speaking instructor in the Ueda Tradition. Ueda Sko Ry Melbourne is active in public events, festivals, artistic collaboration, and more sophisticated internal tea ceremonies.

Explanation of Ueda Soko Tea

In feudal Japan, chanoyu (tea ceremony) and Zen were widely practised and held in high esteem by the samurai. 'Bukecha' (pronounced Bu-ke-cha) or 'Samurai Tea' pursues harmony in the seeming polarity of Wabi aesthetics and ostentatious displays of power. In feudal times the Samurai lived with an acute sense their death could arrive in any moment. The spiritual longing, quietude and embrace of imperfection coiled up in Wabi resonated with the samurai. The central values of Samurai Tea are finding calm for one's mind amongst the turmoil of everyday life, cultivating a reverence for nature, and the conviction to live every moment with purpose. The Japanese tea ceremony is an art that developed from the practice of tea drinking in Zen temples. In a tea ceremony, powdered green tea or matcha is prepared in front of guests according to a highly structured procedure. Chanoyu is said to be the physical embodiment of the tranquil mind state and values involved in Zen practice.

The Ueda Soko Tradition places particular emphasis on developing the sincerity of the host; developing a reverence and joy for one’s own life, developing Zen values through all the activities of the tea ceremony; and cultivating beauty that is austere, minimal, yet elegant. Tonight’s ceremony is comprised of straight lines, actions in harmony with the breath, and samurai practicalities such as the purifying cloth (fukusa) on the right of the obi so the host can quickly attach their katana sword (always left on the obi) should they be called to combat. http://uedaryumelb.com

Philip Flavin graduated from the Seiha Conservatory in Tokyo and studied koto under Yuize Shin’ichi and jiuta shamisen under Inoue Michiko. He pursued a performance career with appearances at the National Theatre in Tokyo, Japanese National Radio and Television. He later entered the graduate programme in music at the University of California, Berkeley and completed his dissertation in 2002. After participating in ARC funded research project at Monash University, Philip now resides in Melbourne and continues to write, perform, and teach casually at Melbourne and Monash Universities. His writings on Japanese music and culture, and his translation work are widely published.

Susan Taylor is a practitioner of Jiuta-mai and improvised dance. “Initially the incongruence of West and East, free dance and proscribed dance, seemed insurmountable, yet it peacefully inhabits my limbs and breath”. Susan went to Japan seeking a form and tradition to add to her 10 years of improvised dance practice, performed with Mangala Dance Studios and Mrs James in Mangarra Rd Camberwell. In Tokyo she studied Jiuta-mai style under Yoh Izumo for five years, finding its subtle reflective soul beautifully matching her own temperament. “Curiously the highly proscriptive choreography (even breath is choreographed) was not restrictive. It proved to me that the creative sense of the individual must enliven even the most proscriptive choreography to create a work of art”. Susan’s Jiuta study was supported by a Japan Foundation scholarship. “Extraordinary serendipity found Anne Norman, Philip Flavin and myself in Melbourne, a ready-made Jiuta and mai ensemble! So of course we perform together.” Susan works as a primary school teacher of Japanese language and has taught improvised dance, and Japanese dance to children, teachers and adults. Susan Taylor is a practitioner of Jiuta-mai and improvised dance. “Initially the incongruence of West and East, free dance and proscribed dance, seemed insurmountable, yet it peacefully inhabits my limbs and breath”. Susan went to Japan seeking a form and tradition to add to her 10 years of improvised dance practice, performed with Mangala Dance Studios and Mrs James in Mangarra Rd Camberwell. In Tokyo she studied Jiuta-mai style under Yoh Izumo for five years, finding its subtle reflective soul beautifully matching her own temperament. “Curiously the highly proscriptive choreography (even breath is choreographed) was not restrictive. It proved to me that the creative sense of the individual must enliven even the most proscriptive choreography to create a work of art”. Susan’s Jiuta study was supported by a Japan Foundation scholarship. “Extraordinary serendipity found Anne Norman, Philip Flavin and myself in Melbourne, a ready-made Jiuta and mai ensemble! So of course we perform together.” Susan works as a primary school teacher of Japanese language and has taught improvised dance, and Japanese dance to children, teachers and adults.

Leigh Sloggett began carving netsuke in 1992. In 1993 he moved to Japan to study netsuke carving under Bishu Saito. Since then his work has been exhibited in museums and galleries around the world, including the British museum and the Los Angeles County Museum, and can be found in many important private collections including The H.I.H Prince Takamado Collection. His Netsuke are also in the collections of both the Museum of Fine Art Boston and the Kyoto Seishu Netsuke Art Museum. In 1997 the Japanese Broadcasting Association (NHK) produced a short documentary about Leigh's netsuke. Various articles have also been written about his work in a range of publications such as the International Netsuke Society Journal and Daruma magazine. Since 1993 his work has been regularly exhibited in Japan with his participation in at least two to four exhibitions there each year. LeighSloggett.com/

Explanation of Netsuke

Netsuke are toggles designed to suspend objects such as small bags and inro (lacquer boxes) from the obi (sash), which is worn with the kimono. They evolved in Japan over three hundred years ago. The original netsuke are thought to have evolved from the use of natural objects such as shells and roots and then slowly developed into intricately carved sculptural objects. Being essentially functional objects they have certain constraints placed on their design.

They must be small enough to pass between the obi and the kimono and they must be compact, without protrusions that could break, or catch on and damage the threads of the kimono. They must have an opening for a cord to pass through, to enable objects to be suspended from them and they must be made from a durable material so that they will not be easily damaged from the rigors of use. These days netsuke are rarely used functionally, however their beauty and uniqueness is still largely attributed to the functional constraints. Contemporary netsuke artists continue to take this into consideration when approaching each design.

back to top

|

![]()

![]()