|

This is a small excerpt from a much longer interview for my book, Electronic

Music Pioneers, published by ArtistPro, and distributed by Hal Leonard

Corporation.

This is a small excerpt from a much longer interview for my book, Electronic

Music Pioneers, published by ArtistPro, and distributed by Hal Leonard

Corporation.

I first met Steve Roach in 1986 when he was a guest on my radio program, “Imaginary Voyage.” He had just completed an east coast US tour

promoting his album, Empetus. Since that time, it has been a real

joy watching his career expand and flourish.

"Born in 1955, the internationally renowned artist, Steve Roach

is constantly searching for new sounds that connect with a timeless source

of truth in this ever-changing world.

Roach has earned his position in

the international pantheon of major new music artists over the last two

decades through his ceaseless creative output, constant innovation, intense

live concerts, open-minded collaborations with numerous artists, and the

psychological depth of his music.

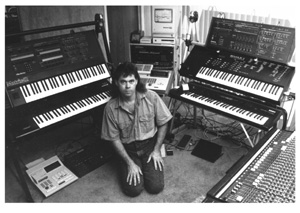

Inspired early on by the music of Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream and

the European electronic music of the 70’s, Steve began his musical

explorations directly on synthesizers at the age of nineteen. He made

his recording debut with the album Now in 1982. Two years later he created

one of the most pivotal albums of his early career, Structures from

Silence, one of the landmark ambient releases of the 80s, presenting

a new sound that lives on today. In fact, the 4th Edition was released

in 2001 by Project. This album was comprised of three long tracks featuring

reflective intimate timbres and cascading lush harmonic waves. Roach sought

to alter the listener’s awareness of their physical surroundings

by increasing the space within each of the pieces, and by extending the

length between the sections to an expansive level, capturing the slow

breath of the silence between the sounds.

Recognized

worldwide as one of the leading innovators in contemporary electronic

music, he has released over 50 albums since 1981: including the 1997 award-winning

live-studio masterpiece, On This Planet, (Fathom); the 1998's critically

acclaimed, Magnificent Void (Fathom); the time traveling Early

Man (Projekt) and a number of albums that are already considered classics

of the genre, most notably the ground-breaking double CD Dreamtime

Return (1988). All of Roach's early works have stood the test of time,

drawing a new generation of fans who are only beginning to discover the

vast territory of sonic innovation this artist has covered over the last

two decades. Recognized

worldwide as one of the leading innovators in contemporary electronic

music, he has released over 50 albums since 1981: including the 1997 award-winning

live-studio masterpiece, On This Planet, (Fathom); the 1998's critically

acclaimed, Magnificent Void (Fathom); the time traveling Early

Man (Projekt) and a number of albums that are already considered classics

of the genre, most notably the ground-breaking double CD Dreamtime

Return (1988). All of Roach's early works have stood the test of time,

drawing a new generation of fans who are only beginning to discover the

vast territory of sonic innovation this artist has covered over the last

two decades.

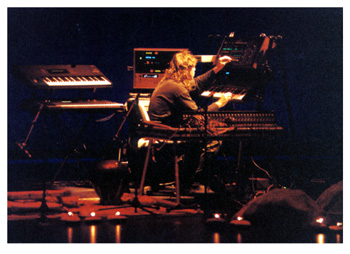

As one of the few electronic-based artists performing live consistently

for over 20 years, Roach's engagements have taken him from concert halls

in the United States, Canada, and Europe, to lava caves in the Canary

Islands and volcanic craters in Mexico. These exotic settings have helped

him further shape his style, a sonic vision that thrives in a sphere of

ritualistic intensity beyond categories, national boundaries, cultural

barriers, and quite often, time itself.

The Interview:

Ben Kettlewell: Many reviewers and listeners describe your music as a

transformational tool, which helps bring the listener into a deeper level

of consciousness. Why do you think so many people share that vision in

regard to your music?

Steve

Roach: The willful intention in all my music is to create an opening,

which allows me to step out of everyday time and space, into a place I

feel we are born to experience directly. Many of our current social structures

and material concerns shut down the opening or build a complex array of ‘plumbing’ to divert a direct experience we all crave in one

way or another. In any case, these sound worlds can offer a place where

the bondage of western time is removed and the feeling of an expanded

state is encouraged. I often refer to the words "visceral,"

being in the "sound current," or "sound worlds", when

describing my work. This is a prime area where I feel the measure of all

my work--in the body. So, for me to create these sounds and rhythms, and

utilize my own body as the reflecting chamber is my direct way of living

in the sound current that occurs naturally when the juices are flowing.

From the feedback I receive, this is something I know receptive listeners

are feeling as well. Tapping into the creative process at this direct

level simply feels like a birthright. Steve

Roach: The willful intention in all my music is to create an opening,

which allows me to step out of everyday time and space, into a place I

feel we are born to experience directly. Many of our current social structures

and material concerns shut down the opening or build a complex array of ‘plumbing’ to divert a direct experience we all crave in one

way or another. In any case, these sound worlds can offer a place where

the bondage of western time is removed and the feeling of an expanded

state is encouraged. I often refer to the words "visceral,"

being in the "sound current," or "sound worlds", when

describing my work. This is a prime area where I feel the measure of all

my work--in the body. So, for me to create these sounds and rhythms, and

utilize my own body as the reflecting chamber is my direct way of living

in the sound current that occurs naturally when the juices are flowing.

From the feedback I receive, this is something I know receptive listeners

are feeling as well. Tapping into the creative process at this direct

level simply feels like a birthright.

I truly feel the complexity of what makes me a human being and drives

me to create this music is something that can never be measured and explained

in terms conveniently reduced to a string of words. Starting with the

impulses and urges of early man, deep in the collective memory up to now,

I feel compelled to make sense of the chaos and beauty around me--to give

it meaning, and feel more whole and alive for our time on this planet.

As far back as I can remember, the realm of ineffable feelings emerging

in everyday life haunted me.

When I discovered the way to express this world through sound, things

just fell into place in many ways. It feels like it's enough to just say

I have to create my music in the same way I have to breathe. It's not

a question of whether it's pleasing or disturbing to other people, or

record companies and so on. I do it for myself before anyone else. The

fact that I have devoted all of my adult life to creating this music at

whatever cost outside the interference of commercial concerns has allowed

me to follow some tracks to places that are essential and universal at

the core. I get the sense the listeners to the music feel this and respond

naturally.

BK: You certainly are a prolific artist. Where do you find the inspiration

and time to create such a great body of output, especially in the past

four years? What inspires you? What keeps you working at this pace?

SR: It's just the natural pace for me to operate at. It's not forced.

I don't feel I'm working at it rigorously. It just feels like I am in

the flow. I love being in this sound current and capturing the music as

I do. It's a constant feedback circuit. Over the years the momentum builds

and the process becomes more rich and fulfilling for me. It's a way of

life for me, not a job or a profession. It's my chosen path, being in

the flow of sound and music. Looking at the flow of a visual artist or

sculptor, for example, these people usually have reams of work in various

stages. A constant regeneration occurs where the work helps build the

momentum and energy that inspires the actual process. It's no different

for me. I've always felt more connected to this process of creativity.

Somewhere along the way, the record industry set a standard to protect

their own investments with an artist or group squeezing out a release

every fifteen months. That system has never really made sense for the

way I work. Now, with the Timeroom Editions, and the outstanding collaborative

relationship with Sam Rosenthal, owner of Project Records with whom I

release my above ground work, I have found a nice flow and balance.

BK: You, Robert Rich, and Michael Stearns were among the first Americans

to delve into this type of music. What was it like back in the 1970s trying

to introduce your music to a new audience?

SR:

It's been a long, wonderful and strange trip indeed. When I set out to

live the creative life as a sound sculptor, it was a different time to

say the least. In the mid 70's, this music was still being born, especially

in the States. SR:

It's been a long, wonderful and strange trip indeed. When I set out to

live the creative life as a sound sculptor, it was a different time to

say the least. In the mid 70's, this music was still being born, especially

in the States.

There were almost no labels, no real radio support, a few underground

magazines, like Eurock and Synapse, the latter of which I also wrote for.

Compared to today, with the Internet as the hub of all things, it was

the dark ages. Imagine trying to hook up with like-minded people or get

your music to people beyond your immediate reach. It was also an incredibly

exciting time with impending changes in the air.

The frontier of consciousness expanding music was clearly growing, and

this impetus was spawning many new instruments and small companies that

often came and went as fast as they appeared. I set out to do electronic

music against many odds, but my passion to live in the sound current was

all that mattered, and this is what drove me through all the highs and

lows and beyond the nay-sayers. At that time, only a handful of people

around me knew what I was talking about when I would start on these born-again

tirades about the "music of the future". There really was a

feeling of being a part of something significant, in a historic sense.

To witness all these changes and to meet and work with many of the people

helping to bring all this together, in such a short time, was nothing

short of fantastic.

Just a few years ago, getting your music onto an LP or a cassette run

was a major accomplishment. Then there were the tasks of gathering names

from underground sources and mailing packages and letters to each and

every one. It was a grassroots effort where I felt like every cassette

or LP sent out was like a personal connection. I still feel this way but

on a larger scale. My first release was Now, in 1982, followed by Structures

from Silence on cassette. It was this release that brought me to the attention

of Fortuna Records, based in California. This is about the time I met

Robert Rich, who was also self-publishing his early work, like Trances

and Drones.

It's important for me to say I have never approached my music as a career,

a profession, or a way to make a living. My obsession to live in these

sound worlds has eventually provided the support to keep me creating.

I survived a lot of strange jobs at that time. One of the better ones

was eight hours a day in a clean room at a Microbiology lab for a few

years. Then straight home to The Timeroom all night, living like a techno

monk in a tiny one-bedroom house in Culver City, Ca. I even had a visit

from Chris Franke of Tangerine Dream at one point, which for me at the

time was pretty much like the Dalai Lama stopping in, at this stucco Gingerbread

looking bungalow built in the 30's for the workers in the film studios

nearby. Every spare penny went toward supporting the equipment habit I

needed to create this music. The fact that I eventually reached the point

where the music in turn supported me enough to quit my day job and live

in the sound current exclusively is something I don't take for granted.

As a side bar, this is a very brief overview from my perspective of events

not long ago--in the pre-internet era. The "commercial" groundswell

started to build in the late 80's. The catchall term New Age was adopted

for the purpose of retail and marketing. This travesty of a definition

started to build momentum and swooped up many forms of unsuspecting genre-less

music at the same time. Companies like Windham Hill and Private Music,

backed by major label clout and greed, continued to build the fire and

find a peak in the early 90's, inspiring dozens of overnight labels to

spew out reams of forgettable "product." In my opinion, this

glut of "product" helped to poison the well to a certain extent

and turned a lot of people off to this music in the end. Still, the momentum

from this time had a positive side, and thankfully, like a raging California

wildfire, it burned itself out, leaving behind a smoldering, ashen heap,

which fueled the natural process of survival of the fittest. The Phoenix

rose up. On the 8th day, what's his name created the Internet, the Mecca

for all fringe dwellers old and new, including the ones that survived

the great "wildfires" of the early 1990s. These events seem

like bumps in the long road when even looking back a few years later.

BK: I want to talk about your method of composition? Is there a chain

of events, or a memory that conjures up a particular sonic image, or do

you go into your studio, and just start exploring ideas?

SR:

There are so many levels at work here. Long-term ideas that build up energy

often start as spontaneous moments in the studio. Sometimes a title or

a word will key me into the deeper storehouse of memories. The ongoing

meditation of working on the various sound worlds will often take me to

places I could arrive at no other way. I have this biological need to

create certain types of zones that have become established in my music.

It's something that wells up time after time, and it's a world I'm compelled

to keep exploring in various ways. SR:

There are so many levels at work here. Long-term ideas that build up energy

often start as spontaneous moments in the studio. Sometimes a title or

a word will key me into the deeper storehouse of memories. The ongoing

meditation of working on the various sound worlds will often take me to

places I could arrive at no other way. I have this biological need to

create certain types of zones that have become established in my music.

It's something that wells up time after time, and it's a world I'm compelled

to keep exploring in various ways.

The biggest influence is living here in the desert. It's a constant generator

that feeds my inner life in many ways. I have no formula since every project

takes on a different shape and set of harmonic sonic-mythic-rhythmic puzzles

to solve and explore. In some settings, the feeling of creating a film

is the best way to compare the process. Shooting the film can be compared

to capturing improvisations and explorations in the moment, then telling

the story by way of editing. Like the texture and grain of the film, the

processing can drive it, slow it down, and sweep one away.... whatever.

Besides the powerful places right here in the southwest, I get tremendous

inspiration from films, along with the visual arts. Since I never really

do songs, the long form pieces are created from many different elements

that, once woven into the fabric, serve multiple purposes in the big picture.

It is always important to remember the instruments are tools to help me

express multi-leveled emotional nuances and states of consciousness. I'm

careful not to let the technology take over and turn me into a more rigid,

machine-like being.

BK: When you’re working on a composition, molding sound, building

things up, how do you sense when the piece is complete?

SR: Gut feeling. Instinct. Creating a flow and balance that just feels

right. Sometimes with a piece that occurs spontaneously, it feels finished

right on the spot. Other times I can work on a piece over a long period

of time before it feels complete. Each piece or final CD had its own story

for me on many levels. Sometimes, I put all of myself into the one I am

currently engaged in, only moving forward when it feels complete. Sometimes

I have several different fires going at once, and they all influence each

other, maybe balancing each other as they express opposite feelings or

sides of my personality. With that said, I can listen to older releases

and hear them from a new perspective. This might trigger a new idea or

technique and sometimes remind me of a path I traveled down for a while

and want to jump back on that track and keep exploring it further and

deeper.

BK: Can you tell me about the Tabula Rasa and how that affects

your preparation for creating music?

SR: Tabula Rasa means "clean slate" in Latin. It is for

me a state of creative nothingness, a mindset that lets go of all preconceived

ideas, habits, social mores, philosophical ideas, obligations, methods

and techniques. While some of my work is influenced by the past, by feelings

I've already explored and want to go deeper into, a piece created from

the Tabula Rasa state has no connection to the past, no connection

to time at all really. It seems to rise up from a place of pure, unformed

potential that leads you into a new way of working and perceiving. I just

create an opening in my mind and my heart and let it happen. Some of my

best work has come from this perspective. These pieces have led me down

an unexpected path, expanding my style and my scope as an artist.

BK: Your albums, Dreamtime Return and Sound of the Earth,

marked quite a pivotal period in your career. Can you tell me about your

meeting with David Hudson, and how your trips to Australia brought all

this together?

SR:

Dreamtime Return was certainly a culmination of my deepest desires

and aspirations up to that point. I came into my own as an artist during

that project. It was really an initiation for me on many levels, including

the connection to my own sound that I was constantly searching out. Most

of all, it was a time of intensive personal growth and understanding.

I felt that I'd left a lot of the overt European influences behind at

that point, integrating them in a more personal way, and my relationship

to land where I grew up deepened. SR:

Dreamtime Return was certainly a culmination of my deepest desires

and aspirations up to that point. I came into my own as an artist during

that project. It was really an initiation for me on many levels, including

the connection to my own sound that I was constantly searching out. Most

of all, it was a time of intensive personal growth and understanding.

I felt that I'd left a lot of the overt European influences behind at

that point, integrating them in a more personal way, and my relationship

to land where I grew up deepened.

The expansive, breathing, warm harmonic waves of sound reflected the desert

landscapes that shaped me when I was young. These sounds, and the sensations

that gave rise to them, were already alive within me; I just had to wipe

the slate clean of European influences to allow this deeper, personal

music to come through. Around this time, the mid-80s, the feeling of a

sonic and spiritual bridge between the Southwest and the Australian outback

was also awakening.

I spent a lot of time in Joshua Tree, outside L.A. in the desert region.

I grew up in the Southern California Deserts, Anza Borrego and others.

From the bedrock of this amazing land of extremes, I began to feel a sense

of spiritual expansion, which grew out from beyond the desert I grew up

in and was inspired by--a much larger, less familiar landscape. This was

when the Dreamtime concept started to unfold.

Around this time I also saw the film by Peter Weir, The Last Wave,

in which I heard the didgeridoo for the first time. It was a white filmmaker's

version of certain mystical aspects of the Dreamtime and Aboriginal culture

in it's own obviously diluted way. But still, it was a significant point

in my growing fascination with Australia. I had a friend who moved to

Australia in the 60's and came back with captivating stories of this faraway

place. The mystery of this ancient landscape spiraled through my subconscious

for years. In the mid 80's I was starting to work on preliminary pieces

for Dreamtime Return, just gathering different impressions with

no idea that I would be going to Australia. I really hadn't thought about

it much more than just fascination about the different deserts out there

that you could travel to in your imagination.

Knowing I was working on this project, the owner of Fortuna Records at

the time, Ethan Edgecomb, sent me a book "Archaeology of the Dreamtime",

about the time I was starting to get deeper into the project, around 1986.

Probably within a month of receiving that book and reading it--which was

written from an anthropological point of view of the Australians Aboriginals

in the Cape York area of Australia - I received a phone call from a filmmaker

who was working on a film called the Art of the Dreamtime. Using that

very same book as a reference, he was producing a documentary for PBS

and planning an expedition to that very same remote area in Cape York

with a film crew from a university. One thing led to another, and I became

the musician/composer on that expedition. They took care of everything

for me, so I was one of the crewmembers. It was just an unbelievable turn

of events. The filmmaker said he first heard my music when he was traveling

to Mexico through Texas and Structures from Silence was playing on the

radio late at night across the desert. I remember him saying that he felt

like he was in a Stanley Kubrick film, and so did I.

The feeling of synchronicity was overwhelming at times. Along with being

in those remote Aboriginal sites for weeks, the entire project brought

up so much in me that went way beyond music. Being at these sites, sleeping

on the same dirt as the ancient people of the land and listening to pieces

on headphones that I'd already created back in the Timeroom before I ever

imagined I would go to Australia was unforgettable.

This was also when I met Aboriginal Didgeridoo player David Hudson, who

I went on to produce three didgeridoo records for. He taught me to play

the didg. The entire Australian-Dreamtime Return period was a tremendous

opening for me as an artist, and as a person. It taught me to really listen

with my ear very closely to the ground, a direct experience of how magical

things can happen when you listen with your heart and an open mind. The

influences of those events continue to spiral out, unfolding with a natural

order. I feel the uninterrupted connection still reverberating from that

point--the understanding that I came to during the two years of making

Dreamtime Return.

By 1989 I was back in Australia for a second adventure that led to the

project, Australia: Sound of the Earth. It was directly after this

second trip to Australia that I moved to Tucson and started a new life

with my wife Linda Kohanov.

A curious side note is that David Hudson came for a visit here in Tucson

in the early 90's with his fiancée Cindy and ended up getting married

in the desert behind my house. He was taken with how much Tucson felt

like Alice Springs, in central Australia, the place where they met originally.

They were inspired by the parallels between the two deserts and how Tucson

was able to bring up similar feelings for them. Since they were on an

extended holiday, they rose to the moment.

BK: You've combined the use of ancient indigenous instruments with high

technology in many of your works. Can you explain the synergy you find

by combining ancient and modern musical tools?

SR:

I see the didgeridoo and my favorite analog synthesizer, the Oberheim

Matrix 12 as both being high points in their own time, created out of

a need to hear and create a sound that the consciousness was needing.

The didgeridoo was a much earlier form of technology, one that created

a rich, continuous drone in the same way as the most current synthesizer

and computer setups. In the right hands, the Oberheim Matrix 12 Analog

Synth can tap into the same timeless realm as the didg, and elaborate

on this feeling with a much more intricate series of multi-layered voices,

creating a harmonic atmosphere that blossoms into waves of sound, seemingly

spilling forth from some other world. The rich, uninterrupted harmonic

drones of the didgeridoo have an almost electronic sound that captivated

me the moment I heard it. The sounds embraced each other so well, creating

this electro-organic quality. I went on to explore this by extensively

fusing all sorts of elemental sounds into the electric stew. The simple

act of having an open microphone recording an acoustic track in the midst

of a full blown electronic piece adds a since of space, injecting "air" directly into what was once a hermetically sealed world. My recordings

Origins and the recent Early Man are prime examples of this synergy. SR:

I see the didgeridoo and my favorite analog synthesizer, the Oberheim

Matrix 12 as both being high points in their own time, created out of

a need to hear and create a sound that the consciousness was needing.

The didgeridoo was a much earlier form of technology, one that created

a rich, continuous drone in the same way as the most current synthesizer

and computer setups. In the right hands, the Oberheim Matrix 12 Analog

Synth can tap into the same timeless realm as the didg, and elaborate

on this feeling with a much more intricate series of multi-layered voices,

creating a harmonic atmosphere that blossoms into waves of sound, seemingly

spilling forth from some other world. The rich, uninterrupted harmonic

drones of the didgeridoo have an almost electronic sound that captivated

me the moment I heard it. The sounds embraced each other so well, creating

this electro-organic quality. I went on to explore this by extensively

fusing all sorts of elemental sounds into the electric stew. The simple

act of having an open microphone recording an acoustic track in the midst

of a full blown electronic piece adds a since of space, injecting "air" directly into what was once a hermetically sealed world. My recordings

Origins and the recent Early Man are prime examples of this synergy.

BK: Do you plan to further explore the DVD format in your future creations?

SR: This medium is a natural extension for the music, which is often quite

visual on it’s own. I have had quite a few visual music pieces in

the past on video and Laser Disk. The merging of music and images has

been a part of my creative process. It appears that DVD is the mode to

parallel if not replace the audio CD in future. Also the possibilities

of the extended program time and surround mixes will become more available

in future music. I am watching closely with sober anticipation.

BK: What are your plans for the future? Where do you see this kind of

music going in the next ten years?

SR: I usually have several projects on the burner at once, usually in

vast contrast to each other, so I am sharing time between these now. I

find they usually feed each other in curious ways during the parallel

creative process. As for a ten year projection, it's up to those making

the music to meet the challenge of having all the tools anyone could ever

ask for while expressing something connected to the bigger picture, something

that comes from a genuine place. I have always seen this indefinable sound-art

as an outlet for the innately talented--for people, who, not too long

ago might never have found a way to express these worlds. This means more

and more people, like myself, who didn't fit into the conformity of the

academic world, or didn’t give in to the bondage of creativity within

the conventional matrix of the music or film business, can express their

own unique visions with true independence. I feel the best qualities of

this music are evolving in exciting ways, in all the sub-genres. It's

a moot point to say the boundaries are dissolving; it's a big boiling

pot by now. I say, just keep stirring it, adding new ingredients and trying

new recipes while staying connected to the soulful qualities that move

one to create in the first place. The good stuff will rise and the rest

will fall away like it always has. One thing for sure is there will be

more of both extremes.

------------------------------------------------------------------

This is a five page excerpt from a sixteen page interview. The complete

interview is featured in Ben Kettlewell's book Electronic Music Pioneers.

For more information on Steve Roach, please visit his website:

www.steveroach.com

This site is copyrighted ®© AMP/Alternate Music Press, 1997-2024. All Rights Reserved.

Unauthorized duplication and distribution of copyrighted material violates

Federal Law. |

![]()

![]()